This week’s theme is…Yet More Syndication! I’m hard at work on more great content for the weeks ahead. Until then, enjoy just a few more of my favorite episodes in rerun 🙂

Yet More Syndication, Day 3 – Symphony N0. 3 “Eroica” by Ludwig van Beethoven

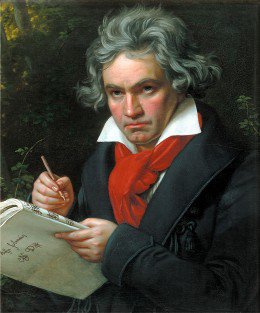

Beethoven could never do anything small, could he? Practically his entire significance is ensconced in the way he expanded the musical forms inherited from the Classical era. Beethoven was an artist who made what he found larger and considerably deeper, and then left as it a challenge for those who came after him . He was larger than life. His passions, his temper, his ambitions, his superhuman willpower, his opinion of his artistry (not entirely undeserved). He dreamed big dreams, thought big thoughts, achieved big goals, and wrote big tunes.

And he loved his coffee in a big way. Have you ever heard about Beethoven’s taste for coffee? Let me tell you! Each and every day, Beethoven would brew himself a cup of coffee made with exactly 60 beans. Exactly. Does that seem like a lot? That’s the commentary I most often find about Beethoven’s coffee formula, that it sounds like a strong cup. At first I thought it did, too, but once I counted it out and measured it I discovered that 60 beans amounts to a little less than a heaping tablespoon, which is about the strength I brew at home.

And I’ve had a hard time finding out exactly how big his cup would have been, so I can’t speak to the precise strength of Beethoven’s brew. I also don’t know what the general strength would have been among his contemporary coffee hounds, so again, not sure how his would compare. But it seems fair to say that the strength wasn’t so phenomenal. It must have been good though. I have read that his guests spoke highly of his coffee preparation and that he became extra-exacting about the recipe with company present. And actually, his neurosis for counting out exactly 60 coffee beans per cup speaks more to OCD, which some people speculate that he was, than caffeine dependence. I also don’t know how much he drank throughout the day, a statistic which is recorded for other figures such as Voltaire (40 – 50 cups of a coffee and chocolate mixture), Balzac (50 cups a day, and later on in life he just ate the grounds) and Theodore Roosevelt (a gallon per day), but as Beethoven’s consumption not written about in such figures I suspect it was moderate.

Anyway, let’s just say Beethoven loved coffee, and in a big way. I think we can agree on that. The method and attention to detail he lavished upon its preparation suggests to me that it was an inextricably significant component of the daily ritual that allowed him, and so many other artists, to create as they did. And, interestingly enough, he wrote one of his biggest, grandest, and most-admired musical works in honor of another larger than life-kind of guy who also loved his coffee, Napoleon Bonaparte. I bet you’ve heard of him. He figured prominently in the history of France. And he loved his coffee. I guess a guy doesn’t wake up and set out to conquer the world without a good slug of morning joe.

Napoleon is recorded to have made statements which indicate more than a passing interest in the beloved liquor, and they range from glib and practical to waxing most poetically. Statements like:

“I would rather suffer with coffee than be senseless.”

and

“Strong coffee, much strong coffee, is what awakens me. Coffee gives me warmth, waking, an unusual force and a pain that is not without very great pleasure.”

Still not quite sure what that last one means. But, whatever. He liked coffee. So, behind every great man is his coffee. I think that’s how the saying goes, right? Well, pretty sure. Anyway, those two larger-than-life coffee-lovers, Ludwig van Beethoven and Napoleon Bonaparte, are metaphysically entangled through the pages of one of Beethoven’s greatest works, the Third Symphony in E-flat major. Most people know it today by Beethoven’s imposed nickname “Eroica”, which means “heroic” in Italian. And it certainly fits. But the moniker “Eroica” actually replaced Beethoven’s previous nickname for the symphony, which was “Bonaparte”. That’s right. Beethoven’s Third Symphony, which many would call his greatest, and even more would call his most influential, was originally named after, and dedicated to, Napoleon Bonaparte.

Beethoven, in the customarily idealistic manner of a true artist, was a fan of the liberal democracies that were popping up in the Western world during his day as a result of the Enlightenment (which some speculate was fueled in large part by coffee-drinking and the exchange of ideas that resulted from coffee house culture). His life coincided with the revolutions of both America and France, and the long wake of France’s tumultuous political upheaval rippled through the events of Beethoven’s later life. He observed the rise of the Napoleon, first shrewdly stabilizing the turbulence of France’s disarrayed government while bolstering his own political power in the process, and then crowning himself Emperor of the new French Empire, before setting about conquer as much of Europe as he could.

Napoleon’s self-styled coronation infuriated and disillusioned the idealistic Beethoven, who removed the dedication upon learning of the ambitious Corsican’s true motivations for seeking political power.

He redubbed the symphony “Eroica” with the subtitle “Dedicated to the memory of a great man”. 15 years later, when Napoleon died, Beethoven remembered the dedication, noting that he had already written a funeral march (the Third Symphony’s dour second movement) for the occasion. I think you could also interpret the subtitle as Beethoven’s continued dedication to the man he once thought Napoleon was, standing for the ideals of equality, liberty and democracy.

The Eroica Symphony is Beethoven’s shot across the bow, launching the Romantic era of music in one fell swoop. It was the longest symphony to date, and by far the most powerful. Beethoven is the first musician in recorded history to so unabashedly express his idealistic nature in his works and the Eroica Symphony seems to convey that clash of civilizations, especially the titanic opening movement. It is Beethoven’s telling of the benevolent forces he once believed to animate Napoleon and the endeavor of the French Revolution. While both of those complicated forces have major skeletons in their closets, existing as they do in our real and imperfect world, Beethoven never lost his sight of the ideals that purported to animate them. Indeed it seemed to grow stronger the longer he lived, culminating in his most idealistic statement of all, the Ode to Joy of his final symphony.

—

Would you like Aaron to provide customized program notes especially for your next performance? Super! Just click here to get started.

Want to listen to the entire playlist for this week and other weeks? Check out the Smart and Soulful YouTube Channel for weekly playlists!

Do you have feedback for me? I’d love to hear it! E-mail me at smartandsoulful@gmail.com

Do you have a comment to add to the discussion? Please leave one below and share your voice!

Subscribe to Smart and Soulful on Facebook and Twitter so you never miss a post!