This week’s theme is…Rondos Old & New! When we hear music, our minds are constantly, and subconsciously, asking a very simple but important question: “is what I’m hearing right now the same or different than what I’ve heard before?” Musicians understand this important principle and so strive to balance the opposing forces of familiarity and contrast throughout their works. Too much of the same will get boring; too little of the same will become incoherent. The traditional forms that have governed music for centuries reflect this, most especially the rondo with its distinctive refrain that keeps coming back after we hear contrasting sections. The rondo has given musicians a basic but powerful and effective way to organize their musical materials in time for almost a millennium. This week we listen to examples from all across history.

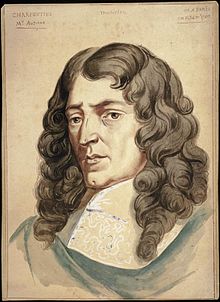

Rondos Old & New, Day 3 – Prelude from Te Deum by Marc Antoine Charpentier

It can’t have been easy to be an ambitious musician in France during the late seventeenth century. Everything you would have wanted to do was, at first, prohibited, and after that restricted. Especially if you wanted to write operas, or, as the French called them, tradegies-lyrique, which translates to something like “lyrical dramas”. This was due to the influence of France’s first great composer, Jean-Baptiste Lully. Read more about him here. But that wasn’t his original name. It was Giovanni Battista-Lulli, and he was Italian. Florentine to be more specific. Florence is actually where opera was born, growing from the efforts of a small club of humanists organized by an aristocrat named Count Bardi, conspiring under the name of the Florentine Camerata. Their first experiments in trying to recreate ancient Greek drama gave birth to the art form that became opera, which proceeded to sweep through Italy, and then beyond. So, you could say that opera was in Lully’s blood, hailing as he did from Florence. Although it would be a little while before he flexed those muscles fully. Lully ingratiated himself to Louis XIV, the Sun King, whose totalitarian nature would work to his great advantage as he reached the pinnacle of his career. Lully proceeded to develop and perfect a number of dramatic musical forms which incorporated acting, singing, and dancing, always yielding an unmistakably French result. And then, in 1673, came his first tragedie-lyrique, Cadmus and Hermione, based on an episode from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the first of thirteen completed by Lully, steadily produced at the rate of roughly one per year until his death.

The tragedies-lyrique have EVERYTHING! Interesting allegorical plots based on mythological stories, sumptuous orchestral music to accompany the singing, a wide variety dance movements to satisfy the French hunger for elegant choreography, and five different acts in each show to present a variety of dramatic and entertaining configurations. I posses a soft spot for them myself and could listen to Lullian tragedies-lyrique for hours. I generally enjoy the style that Lully came up with, find it deeply satisfying in a way, and also like the music written by his contemporaries and followers which seek to imitate that style. And I enjoy it even though it is thinly-veiled propaganda, always serving to glorify the life and reign of the Sun King. You could get turned off by that if you think too much about it, but at the same time you can’t blame Lully given the professional benefits that came along with that line of work. Louis XIV was just the kind of monarch to reward that kind of loyalty and praise with a minor token of his appreciation, like a total monopoly on writing and staging operas in the entire country of France. That’s right: no one besides Lully had the legal right to compose or produce tragedies-lyrique on the Sun King’s watch. The man must have become exorbitantly wealthy (as wealthy as a servant could become). And, while it’s easy to judge Lully harshly for taking advantage of this cushy arrangement, we should not lose sight of the fact that he did invent the style. Without Lully there would not be French art music, or it would look quite different, and may not have worked nearly as well. Lully’s importance is not to be underestimated, nor is his business sense.

But it can’t have made life easy for other French musicians, particularly any who wanted to compose their own operas, or break away from Lully’s style in any way. Even after his death, revivals of Lully’s operas dominated French stages for 50 years. Jean-Philippe Rameau’s first opera Hippolyte et Aricie, cast in a similar form, but musically quite different, started an outright culture war between musical conservatives, who thought Lully’s model should not be touched, and progressives, who saw a breath of fresh air in Rameau’s musical language, when it premiered in 1733, 46 years after Lully’s death. Up to this point, all operas composed in France basically sounded like copies of Lully. But it is interesting to listen to some who copied Lully’s style out of necessity. It is a most effective style, fitting the French character and language, and providing a solid and functional vocabulary of idioms in which other composers could work, whether they wanted to or not.

One such musician was Marc-Antoine Charpentier, just a few years younger than Lully. Had Lully not exercised his monopoly, Charpentier, and others like him, would probably have left more operas, but as it was they were very difficult to produce. Charpentier’s Medee was not staged until he was 50 years old, and it is a masterpiece. Some say he was Lully’s equal, if not superior. In Charpentier I hear the style of Lully, but with an ease, a grace, a fluency, and a level of control that often transcends Lully’s sometimes stiff and stodgy manner. No wonder the older composer felt so threatened.

Charpentier, then, focused on non-operatic vocal forms, and sacred music. There were models from Lully in the arena of sacred music also, but no monopoly (which probably would have been difficult to secure and less profitable). One of Charpentier’s best-known sacred works is his splendid Te Deum in D major. He composed six motets on that text, and of those four survive. This is the most famous. Throughout the varied vocal and choral movements of the episodic work Charpentier captures with ease a wide variety of the idioms and textures that make Lully tick. If you know Lully’s tragedies-lyrique you can listen to Charpentier’s D major Te Deum and pick out many of his greatest hits. In this context the style works well, evoking the splendor of the French court in a liturgical setting.

The prelude is justly famous for its pompous march-like quality. One can almost imagine the rich, visual pageantry of a royal procession for Louis XIV. And it is a clear rondeau, one of Lully’s preferred dance forms, and one that he helped to popularize and spread. In the hands of Lully and his imitators the rondeau, respelled rondo by Italians and Germans, became exceptionally clear in its discrete sections taking on the form ABACA. The B and C section “couplets” are often more lightly orchestrated, and C is in the relative minor. They happen in close succession and so are very easy to hear. Here is Marc Minkowski’s brisk interpretation of the opening rondeau. He adds a brilliant touch: a repeat of the final refrain (A section), which I think balances the work nicely, and which I always add whenever I play it myself. See if you can follow the form, if you aren’t swept away and find yourself dancing along to Minkowski’s zesty tempo 🙂

—

Would you like this featured track in your own personal collection to listen to anytime you want? Support the Smart and Soulful Blog by purchasing it here:

Or purchase the whole album, an exceptional value, here:

Want to listen to the entire playlist for this week and other weeks? Check out the Smart and Soulful YouTube Channel for weekly playlists!

Do you have feedback for me? I’d love to hear it! E-mail me at smartandsoulful@gmail.com

Do you have a comment to add to the discussion? Please leave one below and share your voice!

Subscribe to Smart and Soulful on Facebook and Twitter so you never miss a post!