This week’s theme is…More Syndication! Enjoy some more of my favorite episodes in rerun 🙂

This post is dedicated to my friend Leigh-Ann Balthazor who loved Liszt (“Franzie”) as long as I knew her. Leigh-Ann passed away before her time in September of 2015.

More Syndication, Day 4 – Transcendental Etude No. 12 “Snow Drift” by Franz Liszt

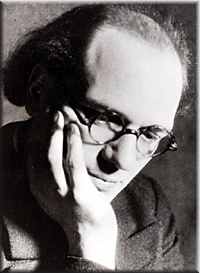

One of my favorite authors of recent years is Malcolm Gladwell, a journalist who wrote three great non-fiction books in the 2000s, The Tipping Point, Blink, and Outliers.

Gladwell has a knack for presenting theories about how the world works and developing them through statistics and anecdotes over the course of a couple hundred pages. His stories are always intriguing and easy to read, and any of these books will have you looking at the world just a bit differently after you finish reading them. And what I find in reflecting on the experience of reading Gladwell after a few years is that, while I don’t remember everything in those books, each of them has at least one major idea or observation about the world that has really stuck with me and continues to resonate with me as I make my way through life. For Outliers it is the 10,000 hours theory, which states that anyone who masters any discipline ends up putting in around 10,000 hours of practice at some point. For Blink it is the way that many of our decisions are made quickly and below the threshold of conscious awareness. And for The Tipping Point it is the idea of the connector.

A connector is a kind of person. By their very nature, it is almost assured that you know at least one of them. They serve a very important role in society. A connector is a person who, in a sense, “collects” acquaintances. They have a way of making lots of somewhat shallow relationships with many, many people. Do you know anyone who has in the neighborhood of 2,000 Facebook friends? They just might be a connector.

Understand that when I say “shallow”, it’s not in a negative or judgemental way. Connectors are simply operating out of their nature, which is to get to know a lot of people. I love the connectors I know, and I think it’s just really neat the way they naturally become acquainted with so many different people. I understand that my connector friends will never be the kind of people I get to know on a truly intimate level, and that’s okay. They serve in important roles, bringing people together, catalyzing social progress, and encouraging everyone to do what they do best. And part of what makes connectors what they are is a sense of affection and appreciation for all the people in their extensive networks.

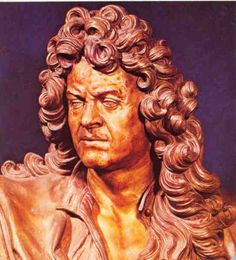

I’ve come to suspect that the renowned Hungarian pianist and composer of the eighteenth century, Franz Liszt, was one of music history’s most important connectors. I think Antonio Salieri may have been another, but that’s a story for another day (interestingly, Liszt and Salieri did know each other and worked together at a certain point in time). Liszt was coming into his own just when the Romantic era of music history could have used a charismatic figure to link its early creators to its later ones, and he, with his tendency to want to meet people, appreciate them, and champion their music, seemed to fit that bill.

Often, when I read about Romantic musicians, I find that Franz Liszt was either a friend, an admirer, or both. It really seems like he made a great and natural effort to get to know every prominent musician in Europe while he was alive and I hardly ever find accounts of him criticizing fellow composers. I think everyone else must have done it at some time, but Liszt really seemed to love everyone, performing and programming musicians of the past, befriending musicians of the present, and encouraging musicians of the future. He was just that kind of guy, and I wish I could have met him for the affection and encouragement!

One of his most important roles was as a conduit of the virtuoso tradition. While he is known for his compositions that added significantly to symphonic repertoire, and even looked ahead to the unsettling harmonic languages of the twentieth century, he was best known during his lifetime as a pianist of astounding virtuosity. In his 20s he had witnessed a performance by the great Italian violin virtuoso, Niccolo Paganini (for more on Paganini, see this post), and at that point resolved to become his equal on the piano, which he did. Liszt and his contemporary piano virtuosi, headquartered in Paris during the 1830s, brought piano technique to unprecedented heights.

His compositions for the piano are an outgrowth of this new pianistic virtuosity. The Transcendental Etudes were published in 1852 after having gone through a long period of development that had started in the 1820s. What came to be known as the Transcendental Etudes were actually based on earlier, more difficult pieces, so perhaps Liszt was reducing their complexity in the interest of opening them up to a wider pool of performers. Still, they are, as the title implies, transcendently challenging, sort of a cross between Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier, with its systematic scheme of keys, and Paganini’s 24 Caprices (see this post) with their encyclopedic catalog of difficult violin techniques, applied to Liszt’s new pianism. They constantly push the piano to its limits, and often paint highly poetic pictures in the while doing so.

The last of the 12 Transcendental Etudes is nicknamed “Snow Drift” and its constant tremolos and sweeping scalar melodies, which constantly switch from hand to hand, and from within the tremolo texture to without, seem to depict a landscape being progressively covered in drifts of snow. Toward the end a new element is added; the tremolos continue, but chromatic scales of very short note values begin to sweep through the texture like swirling winds upsetting the snowbanks. The frenzied climax that follows takes the piece to even more dizzying heights of virtuosity as the wind grows stronger and finally abates.

From what I have heard this is among the most difficult, and also the most stunning of the Transcendental Etudes. Like Paganini’s Caprices, these works that once seemed unplayable (and still do to many people) eventually came to be mastered by many subsequent virtuosos. I have to imagine that Liszt would have taught and encouraged many of them himself, being the connector that he was. Romantic musical Europe would have been a much different place without him in the mix, for his virtuosity, his creative mind, and his magnanimous sense of camaraderie, which he dispensed generously to the other musicians he encountered. He was not content to keep the prestige to himself and clearly understood that the world of music would be a better place with him supporting his fellow musicians rather than suppressing them. For this laudable quality, and others, I am thankful for the life and work of Franz Liszt.

—

Would you like Aaron of Smart and Soulful Music to provide customized program notes especially for your next performance? Super! Just click here to get started.

Want to listen to the entire playlist for this week and other weeks? Check out the Smart and Soulful YouTube Channel for weekly playlists!

Do you have feedback for me? I’d love to hear it! E-mail me at smartandsoulful@gmail.com

Do you have a comment to add to the discussion? Please leave one below and share your voice!

Subscribe to Smart and Soulful on Facebook and Twitter so you never miss a post!