This week’s theme is…Shining Silver! Silver gleams and glistens. It’s gold’s sleek, slick, and stylish cousin. Where gold holds court, silver courts. Silver has driven the history of the world just like gold, and appears in music in many different ways. This week, we look music on which silver has left its dapper lustrous.

Shining Silver, Day 1 – Silver Spray Schottische by John Philip Sousa

Lest you’ve been living under a particularly heavy rock, or if you don’t live in the United States, you’ve certainly heard this:

And, if you’ve been living beneath said heavy rock, you probably haven’t heard this either:

During the nineteenth century the celebrated Can-Can had grown out of the Quadrille, a lively and square social dance.

The Can-Can was probably a social dance at one point too, but eventually morphed into the form we know today, an upbeat and quasi-scandalous dance in 2/4 time which tends to feature a chorus line of ladies in frilly dresses and, perhaps, tights that are just a little too revealing. The Can-Can of his daring comic masterpiece, Orpheus in the Underworld, the best-known of Jacques Offenbach’s almost 100 operettas, is actually something of a misnomer. The hit tune is called a gallop in its original context, an almost sacrilegious send up of the Greek Orpheus myth so dear to musicians. Offenbach achieved notoriety here, and elsewhere, in slaying sacred cows. He was obviously a keen student of the “all publicity is good publicity” public relations school, although his business acumen occasionally left something to be desired, hence his visit to the United States in the 1870s to make some much needed profit. We’ll continue that story in a few paragraphs, but first, some necessary historical exposition…

The second half of the nineteenth century was a checkered time for European music, a time which bore dramatic stage works of two extremes, almost diametrically opposed (and with other styles in between), both of which have proven extremely influential to succeeding musicians. One extreme was Wagnerian opera, with its heavy, Germanic philosophy, powerful singing, and dense, intoxicating harmonies. You can read more about the story of Wagnerian opera here. Wagner’s legacy would inform the next generation of Germanic musicians to compose dense, serious symphonic and operatic music on a grand scale, in the process fueling a tragic unfolding of German nationalism that culminated in the Naziism of the 1930s. On the other extreme was the glittering light music composed for French comic stages, written by the likes of Bizet and Offenbach, and grand Viennese ballrooms composed by Johann Strauss and those of similar ilk. These lighter styles informed the composers who would create light operas throughout the end of the Romantic era and the American musical theater, and also the smaller forms like dance music and marches throughout the Western musical world.

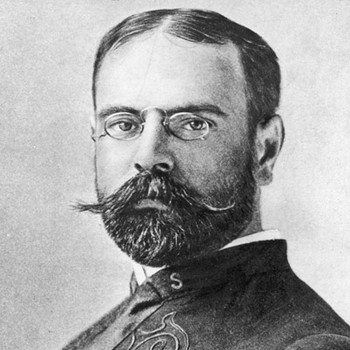

Anyway, back to Offenbach. Or, Bach to Offenbach? Incidentally, I didn’t know he was German born and later personally naturalized by Napoleon III, although if I had really considered his name that may have become obvious. But it seems that the French love their foreign-born but naturalized opera composers – see this post. Anyway, in 1876, largely out of financial necessity owing to losses on recent productions in France, Offenbach visited the United States to present a series of 40 concerts in New York and Philadelphia, which made him a bit of money. Not as much as he had hoped, but it certainly proved to be worth the effort. Playing in his Philadelphia orchestra was an accomplished 22-year old violinist who is now best known for his rich production of patriotic wind band music, the Marine Band Conductor John Philip Sousa.

Sousa is of course now known only for a small handful of his many marches, composed steadily over the course of his lifetime which spanned the final half of the nineteenth century and first third of the twentieth. Given this vantage point he would have been well positioned to observe the German harmonic journey from Schubert to Wagner to Schoenberg, which he could not have helped but to notice, although his output was guided by other aims which found their inspiration in the light operettas of Offenbach and Sullivan, as well as the aristocratic dance music of Johann Strauss. His marches, more than any other body of work, seem to encapsulate the emerging color of American patriotism as the fledgling nation found its firm footing within the balance of international politics and military power. There is still nothing as distinctly “American” as a well-wrought Sousa march. And their number, 136, seems staggering to many of us today, especially given their consistent quality, workmanship, and character which mixes martiality and lyricism in equal and effective measure.

I once taught a music appreciation class to a group of adult nursing students who were fulfilling their humanities requirement, a thoroughly enjoyable experience for all of us, and one of them expressed his amazement at the level of both the quality and sheer productivity that is evident in Sousa’s output of marches. I compared it to that of the great (and lesser) Baroque and Classical composers, all of whom churned out their lovely and perfect music day after day, but even I did not realize at the time that Sousa’s marches are only the tip of his iceberg. Skim through his complete catalog here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_compositions_by_John_Philip_Sousa

Astounding, no? In addition to his ubiquitous marches there are operettas, suites, light concert fare, and numerous arrangements for the various groups he organized and led. And as a performer he did not sit still. After founding his own personal band at age 38, he proceeded to lead them in almost 16,000 performances over the course of their 39 year run, an average of over 400 performances per year, more than one a day. How productive have you been today? 😉

One of the genres in which Sousa was active was dance music. Here is an example of an American flavored Schottische which found its way from its native Bohemia to the United States by way of Victorian England, which had a penchant for Bohemian social dance. Called “Silver Spray”, perhaps as an allusion to the ocean – maybe it was first danced at some kind of coastal resort? – Sousa penned the hyperactive promenade in 1878, just two years after he played under Offenbach’s baton in Philadelphia. At age 24, Sousa was already a masterful composer. More and more today, archive-minded labels like Naxos are turning to the little-known corners of musical history and unearthing their riches, like Sousa’s “Silver Spray” Schottische:

—

Would you like Aaron to provide customized program notes especially for your next performance? Super! Just click here to get started.

Want to listen to the entire playlist for this week and other weeks? Check out the Smart and Soulful YouTube Channel for weekly playlists!

Do you have feedback for me? I’d love to hear it! E-mail me at smartandsoulful@gmail.com

Do you have a comment to add to the discussion? Please leave one below and share your voice!

Subscribe to Smart and Soulful on Facebook and Twitter so you never miss a post!