This week’s theme is…Music about Trees! Trees are noble, beautiful, helpful when we need them, and otherwise on the periphery of human drama. Still, they are always there, forming our landscape, and providing poetic inspiration for artists and musicians.

Music About Trees, Day 3 – Pines of Rome by Ottorino Respighi

If you know me at all then perhaps you also know that I have amassed a considerable collection of classical recordings over the past couple decades. They’re all on compact disc, and they take up some space, but I don’t think I’d ever sell them because there’s just something different about possessing the tangible goods than there is about having a hard drive full of files. Compact disc albums, like vinyl before them, have production value which yields an aesthetically satisfying physical product that accompanies the more metaphysical satisfaction of the music contained therein. On a related note I once heard about someone who challenges people with questions like, “Would you bequeath your collection of books to your kids? What about your Kindle?” His point is that the thoughts provoked by that question indicate an obvious difference in most people’s minds as they consider the experience of inheriting an iPod versus a CD collection, and it is a difference I have long respected. They may take up space, and I may not use them that often, preferring to click within my iTunes library to going through the process of finding an album and putting the disc in the player, but the cultural heritage the physical objects represent is invaluable.

I have taken the attitude of a collector since middle school, when I made the semi-conscious decision to begin my acquaintance with classical music. It has been well worth the effort, and I have often found myself acquiring items that seem worthy of collection even if I do not end up listening to them for a long time. Still, they are there to discover years later, waiting to be engaged with a knowledge base and maturity that were absent when they were acquired.

So it is with this album:

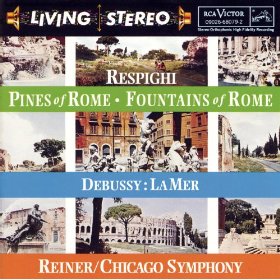

I probably ordered this when I was in high school, perhaps 20 years ago, and maybe listened to it once before today. Seriously! And what a treasure I discovered it to be. A few months ago I played in a performance of Debussy’s La Mer (for more information about that incredible work, see this post). I am happy to say I will no longer live unacquainted with La Mer. I understand that to be a work to which I can return for my entire life for incredible satisfaction and inspiration. And La Mer is a significant work; I’m fairly sure it impacted the way that much orchestral music was created in Europe after it gained popularity in the early twentieth century, within the few years after its turbulent premiere. This album is a good case in point. Take another look at the cover and see if you can digest the contents.

You see 2 pieces by Ottorino Respighi, an Italian composer, active mostly during the early twentieth century, Pines of Rome and Fountains of Rome, and one by Claude Debussy, a French composer active just a little earlier than Respighi, but also very much at the same time, the aforementioned La Mer. At some point a producer or programmer made the decision to create a program with those three pieces, and that is a significant fact. Because from a cataloguing point of view it would have made more sense to program, not Debussy’s La Mer, but Respighi’s Festivals of Rome, which completes the “Roman Trilogy” that includes Fountains and Pines. Now, Pines of Rome and Fountains of Rome are more commonly programmed and better-known than Roman Festivals, but I’m sure the Chicago Symphony Orchestra was up to it had they wanted to program the complete Roman Trilogy on this single disc. So, why include Debussy’s La Mer instead? And why does Debussy’s La Mer, which appears at the beginning of the disc, before the Respighi selections, seem to pair so easily with the Fountains and Pines of Rome?

I think it’s because Debussy’s approach to crafting orchestral music, often described as Impressionistic, like the paintings, was incredibly compelling and influential to many musicians who lived and worked during and after his lifetime. Debussy’s uncompromising approach, which changed the face of all genres he touched, saw him regarding the symphony orchestra as a great palette of evocative colors which, when combined with an equally colorful palette of exotic-sounding scales, created music of unprecedented nuance of texture and gesture. It is notable that very few of Debussy’s compositions fit the definition of “absolute music”. I first encountered discussion of absolute music when I saw Disney’s Fantasia as a child. The master of ceremonies, Deems Taylor, narrates extensively between the different selections, describing historical and aesthetic ideas which the filmmakers considered helpful for their audiences’ appreciation of the musical selections. Incidentally, you can find much of Taylor’s narration transcribed here. Taylor defines “absolute music” as:

“…music that exists simply for its own sake. Now, the number that opens our “Fantasia” program, the “Toccata and Fugue” [by J.S. Bach, orchestrated by Leopold Stokowski], is…what we call “absolute music”. Even the title has no meaning beyond a description of the form of the music. What you will see on the screen is a picture of the various abstract images that might pass through your mind if you sat in a concert hall listening to this music. At first, you’re more or less conscious of the orchestra. So our picture opens with a series of impressions of the conductor and the players. Then the music begins to suggest other things to your imagination. They might be, oh, just masses of color or they may be cloud forms or great landscapes or vague shadows or geometrical objects floating in space. So now we present the “Toccata and Fugue In D Minor” by Johann Sebastian Bach, interpreted in pictures by Walt Disney and his associates, and in music by the Philadelphia Orchestra and its conductor, Leopold Stokowski.”

Most great classical music of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries is absolute music, although its opposite, programmatic music, became more popular in the nineteenth. But once Debussy found his mature voice, he did not write all that much absolute music. It seems that Debussy was always wielding his evocative colors and harmonies to paint pictures of some kind. Every single one of his great orchestral works is labelled by some extra-musical association. Here’s Leonard Bernstein describing his interpretation of one such movement, the astounding Festivals from Debussy’s Nocturnes. You can skip to about 6:00.

This performance is part of a presentation about modes, which are a kind of scale that Debussy, and other musicians, used to create certain effects. If you are interested in that you can of course watch the whole video and its three other parts (it’s pretty fun, but I’m into that kind of thing). But did you notice the rather blurry and yet wonderfully vivid way that Debussy evokes images of the subjects Bernstein described? Nothing had quite felt this way until Debussy, but many other composers, upon witnessing the fruits of his artistry, were inspired to create similarly evocative pieces that worked in much the same way, even if the melodic and orchestrational style were not precisely Impressionistic as Debussy’s was.

I think Respighi’s Roman pieces, composed a couple decades after Debussy’s great orchestral works, operate more or less in the same vein. Even though their melodic edges tend to be clearer and sharper than Debussy’s, they evoke their pictures in much the same way. See if you don’t agree in listening to the first two movements of Pines of Rome, which presents musical portraits of pine trees in various places in Rome. It’s the activity around the pines that is significant to Respighi’s musical telling, and their descriptions feel much like Bernstein’s narration of Debussy’s Festivals.

The first movement portrays children playing by the pine trees in the Villa Borghese gardens. The great Villa Borghese is a monument to the patronage of the Borghese family, which dominated the city in the early seventeenth century. It is a sunny morning and the children sing nursery rhymes and play soldiers:

The second movement is a majestic dirge, conjuring up the picture of a solitary chapel in the deserted Campagna; open land, with a few pine trees silhouetted against the sky. A hymn is heard (specifically, the Kyrie ad libitum 1, Clemens Rector; and the Sanctus from Mass IX, Cum jubilo), the sound rising and sinking again into some sort of catacomb, the subterranean cavern in which the dead are immured. Lower orchestral instruments, plus the organ pedal at 16′ and 32′ pitch, suggest the subterranean nature of the catacombs, while the trombones and horns represent priests chanting.

You can listen to all four colorful movements of Pines of Rome here:

—

Would you like Aaron to provide customized program notes especially for your next performance? Super! Just click here to get started.

Want to listen to the entire playlist for this week and other weeks? Check out the Smart and Soulful YouTube Channel for weekly playlists!

Do you have feedback for me? I’d love to hear it! E-mail me at smartandsoulful@gmail.com

Do you have a comment to add to the discussion? Please leave one below and share your voice!

Subscribe to Smart and Soulful on Facebook and Twitter so you never miss a post!