This week’s theme is…Music for Strange and Rare Instruments! If you hear the term “musical instrument”, chances are that examples from a certain list will enter your imagination. But those are just the ones that made it big. The fact is, the art of the musical instrument teems with near-infinite possibility and many of them slip through the cracks. Sometimes, however, they manage to ignite the imaginations of composers before, or even after they do. This week we explore some of these instruments.

Music for Strange and Rare Instruments, Day 2 – Ballet music for Cavalli’s “Xerse” by Giovanni Battista Lulli

When Wagner took the opportunity to have his opera Tannhauser staged in Paris in 1861, he knew he would have to bite the bullet and make a concession that he wasn’t crazy about. But the opportunity was too valuable to pass up. By this time the composer of the The Ring of the Nibelungen and Tristan and Isolde had fought long and hard to be recognized for the genius that he was. And now his labors were finally paying off, but maybe he could never have anything quite on his own terms. The Bayreuth Festival, which would premiere 15 years after the Paris version of Tannhauser, while representing the ultimate realization of Wagner’s vision, was never entirely free from financial or logistical complications in his lifetime (see this post). And even though Wagner was invited to stage Tannhauser in Paris, a city whose adulation he had worked so hard to win decades earlier, by Napoleon III no less, this was subject to conventions the French expected, conventions that Wagner, the champion of “total artwork”, which eschewed any trace of artifice or contrivance, would have considered trite, stiff, and synthetic. But in this case the usually iconoclastic Wagner knew it would be foolish to stand too firmly on principle – even a personality of his strength could not win against centuries of firmly-rooted convention – and so he composed a ballet for Tannhauser (among a large handful of other changes which changed the structure of the opera), thus making it acceptable for the ultra tradition-minded French.

He still managed to make it somewhat on his own terms though. Whereas it had been the standard practice to insert the ballet in the second act, Wagner chose instead to place it immediately after the overture, as sort of a prelude to the first act. Ever concerned with dramatic integrity (he had, after all, completed the first music dramas which would seal his legacy by this time), he simply couldn’t justify tarnishing the flow of the drama any more than necessary simply for the sake of silly traditions. Whereas French writers had been accustomed to placing ample opportunities within their opera libretti for almost 200 years (see this post to see how that all started), Wagner, one of the first opera composers to write all of his own libretti, was simply not working from that sensibility. As far as he could see, the ballet would serve Tannhauser best by extending the sensuous orgy implied at the very beginning of the opera, which finds the title character ensnared within the hedonistic delights continuously transpiring within the realm of the goddess Venus. Sirens, nymphs, naiads, Bacchantes, all of the most Dionysian supporting characters of mythology make an appearance here. Wagner extended this first scene into a stunning bacchanale, effectively injecting an opulent style of writing informed by his mature operas into this earlier one:

I have to figure that a 25 year-old Camille Saint-Saens, already a supporter of Wagner at this age, even if he was not himself a Wagnerian, attended this performance and channeled the inspiration he experienced from the ballet into the famous bacchanale of his own opera, Samson and Delilah, which bears some similarities to Wagner’s, sixteen years later:

Wagner couldn’t escape the gravity of France’s considerable operatic tradition. It had been that way for centuries. From the beginning of French opera, namely those composed by Lully, ballet had been an inextricable gene , completely integrated within its organic structure. The newly naturalized Lully (he was actually Italian) began to generate his mature French operas in the 1670s, with Cadmus and Hermione premiering in 1673, but an incident a decade prior to that, and almost exactly two centuries prior to Wagner’s Parisian Tannhauser substantially foreshadowed the features that would be present in fully-developed French opera.

The new music dramatic form now called opera was invented around the year 1600 and rose to prominence, due in large part to its masterful treatment by a masterful musician, Claudio Monteverdi (see this post and this one). Without Monteverdi’s very imaginative and practical essays in the genre, which demonstrated to European audiences its great potential for both entertainment and political promotion, opera would have remained a good idea and quickly died. All the best early operas come from his imagination. His death in the 1640s left the artform in the hands of his successors, including Italian musicians like Antonio Cesti and his student Francesco Cavalli. Both Cavalli and Cesti were instrumental in exporting the very Italian art of opera beyond the borders of its homeland. Cesti’s greatest triumph was an opera called The Golden Apple, presented in Vienna (see this post). In 1660 Cavalli was invited to Paris, a peculiar polyglot culture at the time.

Cardinal Mazarin, an Italian, was ruling by proxy as the young Louis XIV was not yet ready, and the native French did not always like him or his sensibilities. But he did his best to acculturate the French with Italian art, hence his invitation to Cavalli. At the same time, however, another Italian named Lulli was already working the Parisian scenes, and already doing as the Romans. He had made friends with the young monarch; they both shared a strong taste for the lyrical dance which came to be known as ballet, with Lulli providing ample amounts of music for them to dance together in performance frequently. As Cavalli entered the Parisian arena Lulli was poised to oppose him as a potential rival, and there is considerable speculation that he and his allies sabotaged Cavalli’s efforts through various machinations of court intrigue. Cavalli was frustrated by much of his experience in Paris, but he did manage to stage one of his operas, called Xerse (for more about that, see this post). Like Wagner’s Tannhauser two centuries hence, it was restructured in various ways to make it palatable to the French, including the addition of ballets. Where Wagner composed his own ballet, however, the ballets for Xerse were composed by the soon-to-be naturalized Lulli. The whole presentation was massive (accounts report anywhere between 6 and 9 hours, either way, beyond Wagnerian) and the French were bored and confused by the Italian opera, preferring Lulli’s episodes, danced by a troupe which included the young king. It must have been a frustrating and humiliating experience for Cavalli.

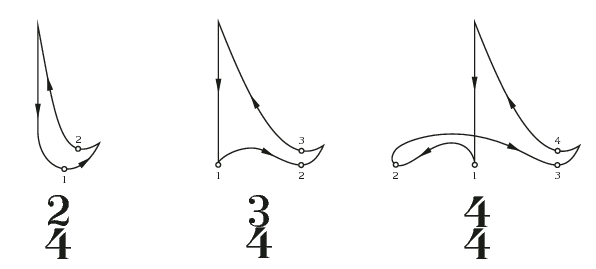

Today, it is just a little more common to encounter the ballet music of Lulli than the Italian vocal music of Cavalli’s creation. Lulli’s stately, elegant music is able to stand apart from the opera. And it is colorful – Lulli included movements with instruments that are today exotic and forgotten, such as the tromba marina. An odd one-stringed instrument, the player bows the single string and uses the fingers of his other hand to travel throughout the harmonic series of the fundamental, much like an unvalved brass instrument, hence its namesake. The sound strikes us as rough, even harsh today, but it as an evocative sound:

The instrument’s inclusion in a sumptuous orchestral texture gives the dance of the sailors a raw earthiness that is more felt than heard on account of the thickness of the orchestra:

Cavalli felt the brutal force of a foreign culture; perhaps familiar with stories such as these, Wagner acquiesced and scored a much more graceful success. Even over the course of 200 intervening years, little had changed in the way of French decorum and national taste; if anything, it had crystallized more. In the decades following Cavalli’s unfortunate Parisian visit, Lulli, now Lully, had formulated a distinctive recipe for composing operas to serve to French audiences based on his considerable experience working in their midst. The resulting tragedies lyrique were aimed precisely to their tastes, always featuring a generous helping of ballet dancing that was skillfully integrated into the plot by French librettists like Philippe Quinault, who supplied the libretti for most of Lully’s operas. This tradition dominated France for centuries, and Wagner understood that when in Rome, he must please the Romans. Cavalli’s earlier trouble perhaps stemmed from his failure to acknowledge that, although it could be argued that it was less clear to him what the Romans wanted anyway. Still, the collaboration between Cavalli and Lulli, as tense as it may have been, is a fascinating story in cultures first clashing, and then synthesizing to form an alloy that endured.

—

Would you like Aaron of Smart and Soulful Music to provide customized program notes especially for your next performance? Super! Just click here to get started.

Want to listen to the entire playlist for this week and other weeks? Check out the Smart and Soulful YouTube Channel for weekly playlists!

Do you have feedback for me? I’d love to hear it! E-mail me at smartandsoulful@gmail.com

Do you have a comment to add to the discussion? Please leave one below and share your voice!

Subscribe to Smart and Soulful on Facebook and Twitter so you never miss a post!