This week’s theme is…Yet More Syndication! I’m hard at work on more great content for the weeks ahead. Until then, enjoy just a few more of my favorite episodes in rerun 🙂

Yet More Syndication, Day 1 – “Sunday Traffic” from The City by Aaron Copland

Have you ever been to a World’s Fair? They’re sometimes called “World Expositions” or “Expos” and I didn’t even know they are still around. But they are. The last one was in May of this year (2015), in Milan, and they actually happen pretty regularly:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_world%27s_fairs

And I had no idea they were still going on! So if you find yourself in Alanya, Turkey in 2016 or Astana, Kazakhstan in 2017, you should definitely drop by and check out the World Expo. Sort of like a mix between a state fair, the Olympics (which moves from world city to world city) and Disney’s Tomorrowland with its better-living-through-chemistry kind of theme, there’s nothing else quite like them. If you are fortunate enough to catch one, I imagine you can expect to be overwhelmed, fascinated and inspired by a colorful mix of exhibitions and forward-thinking ideas.

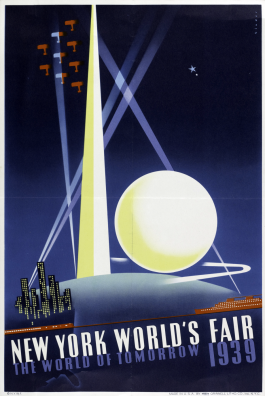

One of the most famous World’s Fairs was that of 1939 in New York City. It was also one of the largest and longest lasting in history. Over the course of its 18-month run, it attracted just short of 45 million visitors from around the world to its array of exhibits and monuments which covered more than 1,000 acres in Flushing Meadows-Corona Park, located in New York City’s borough of Queens.

While the intention of the masterminds behind the 1939 World’s Fair was to revitalize America’s sagging spirit and economy, both hampered by the Great Depression, the event and its distinctive architecture have transcended their original intention to become iconic of the American sensibilities that gave rise to the Baby Boomer generation, technologically forward-looking yet culturally retrospective. The famous Trylon and Perisphere structures, evoking a naive sci-fi feeling, set the visual tone for the fair’s theme, The World of Tomorrow.

The fair was full of evocative architecture, events and exhibits in accordance with that theme, including: “Futurama” (no, not that one!), the Westinghouse Time Capsule (not to be opened for 5,000 years), an enormous ceramic sculpture of an atom, and the world’s first science fiction convention. One of the lesser-known exhibits was a short film created by the American Institute of Planners, a professional organization for urban planners, called The City. Created in 1939, this 30 minute black-and-white film is, by many an evaluation, closer to a propaganda piece than a true documentary. But it is a fascinating piece of vintage filmmaking. Cast in 3 acts, it celebrates the farm life of yesteryear, decries the dehumanizing effect of the sprawling, unplanned industrial-age cities that have grown out of control, and finally suggests a wholesome alternative in planned communities that are able to harmonize modern conveniences with the tranquility of the past, very much keeping in line with the 1939 World’s Fair’s theme of The World of Tomorrow. Actually, these planned communities celebrated by the AIP’s film were not entirely in the future. Examples of these “Greenbelt” communities (so named for the ring of public-held forested land encircling the towns that would keep the landscape green and ensure a perpetual size and shape to the urban landscape) had been established during the 1930s with one each in Wisconsin, Ohio and Maryland.

Carefully planned to balance residential and commercial zones, and always encircled by a belt of green to insulate from the surrounding urban jungle, these small towns were created by New Deal bureaucracies that set income levels for for their residents and and designed them to run as cooperative communities. The concept is highly idealistic, but it seemed to work for these towns. After about a decade the lands, initially owned by the federal government, were gradually sold to the towns’ inhabitants. These communities really could not have been built during any other decade or in any other political climate. In learning about them one senses they are permeated through and through by New Deal philosophy.

This functional idealism comes through very clearly in The City, with its stiff but florid narration, and especially the filmmakers’ choice of composer, a highly significant American musician who, at this time, was busy establishing a populist manner of composition for American listeners, Aaron Copland. Coming to maturity in the 1920s, Copland at first gravitated to the spiky avant-garde stylings popular in Europe around that time, but eventually tired of it and, after settling more permanently in his native land, began to create a more accessible and distinctly iconic American style of music starting in the 1930s. All of his best-known Americana works are written in this style and were created during the late 1930s and early 1940s. These include Appalachian Spring, Billy the Kid, Rodeo, and the stirring Lincoln Portrait. All of these beloved scores successfully fuse the lyricism of American folk song (either authentic or keenly imitated) with an infectious rhythmic drive, broadcast through remarkably clear and astringent orchestration, even during the busiest passages. There are also noble sections of calm, flat terrain that seem to simultaneously evoke both the sweeping amber waves of grain, and the clean, imposing monuments of Washington D.C. And the small group of film scores that Copland composed during the 1930s and 1940s, Hollywood and otherwise, presented one ideal venue to present this new American aesthetic.

The City is a fine showcase of all of Copland’s colors and moods. You can watch the full 30 minute film here and get a sense of everything he could do:

One of the most infectious sections of the score is called “Sunday Traffic” and it comes right at the end of the second act. While the beginning of the act is demoralizing, drab and depressing (intentionally so), this section seems to add comic relief, illustrating the foibles and frustrations of driving on crowded urban freeways:

Copland’s musical accompaniment to this scene is a scherzo, placing madcap and tuneful motives above rhythmic vamps. The variety of orchestral textures is really clever and this little episode of the film score sparkles with with wit and finesse. It also contrasts brilliantly with the Americana nobility that follows as we are shown the soaring images of technological advancement which leads to the third act, begun by the narrator describing how science can help us build cities well-suited to our human nature. Copland’s music for this final act is idyllic but also fast-paced, effectively capturing the onscreen subjects.

Copland was not the only composer to have music featured at the 1939 World’s Fair. Ralph Vaughn-Williams and Arthur Bliss both received commissions for original concert works in association with the fair. But Copland’s contribution, while less centrally-featured, is arguably better suited to the flavor of fair than either of the others. Distinctly forward-looking, toward a bright new generation, Copland’s emerging Americana is congruent with the theme of the fair in ways that the other musics simply could not have been. And, given that this film would have been screened continually, Copland’s score would have had the added benefit of being played nonstop over the course of the World’s Fair’s run of almost two years. This fascinating little film presented itself in so many ways as an ideal vehicle for Copland’s distinctive musical voice.

—

Would you like Aaron to provide customized program notes especially for your next performance? Super! Just click here to get started.

Want to listen to the entire playlist for this week and other weeks? Check out the Smart and Soulful YouTube Channel for weekly playlists!

Do you have feedback for me? I’d love to hear it! E-mail me at smartandsoulful@gmail.com

Do you have a comment to add to the discussion? Please leave one below and share your voice!

Subscribe to Smart and Soulful on Facebook and Twitter so you never miss a post!