This week’s theme is…Music about morning and sunrise! Every day is like a gift, a chance to start anew and clear away whatever happened on the previous one. The gift is always announced by yet another appearance of an old friend, the sun, who rises to greet us in the morning. Because of our subjective view of astronomical features the sun seems to rise in the morning, first filling the sky with dawn’s glorious painting, keeping us in suspense, and then finally showing itself in full splendor. This has been an inspiring image for many musicians who have sought to illustrate that cycle through sound. This week we look at a variety of such examples.

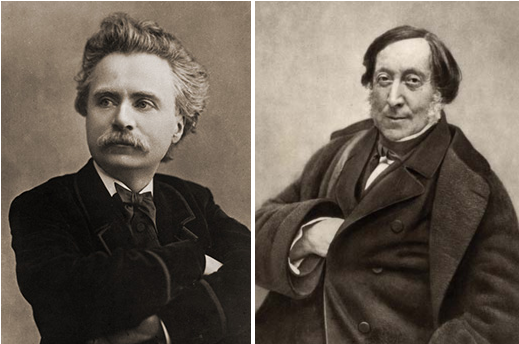

Music about Morning and Sunrise, Day 3 – BONUS Double Post! “Morning Mood” from Peer Gynt by Edvard Grieg and William Tell Overture by Gioachino Rossini

Do you know this character?

Do you know who gave Rocky his voice? Her name is June Foray, and she is one of the most prolific voice actresses in twentieth century America.

How about this character?

His voice was first given by an actor and impressionist named Daws Butler, another highly prolific comic voice actor. Butler was also a notable mentor to vocal talent of the next generation, including Nancy Cartwright, the famous voice of Bart Simpson.

If you do a brief scan through the Wikipedia pages of June Foray and Daws Butler you will begin to develop a sense of just how prolific they were and how much of the voice acting they were responsible for during America’s golden age of comic animation. You could write volumes about their work and the characters they brought to life. But for me and my family, one of their most delightful projects was in their collaboration with an increasingly obscure American radio comedian, Stan Freberg.

If you’ve seen Disney’s Lady and the Tramp, you have heard Stan Freberg voice the beaver who is manipulated into freeing Lady from her muzzle. That’s probably his most famous role today. Incidentally, he was also invited by George Lucas to audition for the voice of C-3PO before the voice role was granted to Anthony Daniels, who also physically embodied the droid onscreen. Oh, if that audition process had followed an alternate path, Freberg’s life after that would probably have looked considerably different (it’s amusing to imagine him on a panel at a Comic Con!). Freberg may have been a bit ahead of his time in many of his endeavors. In addition to his abundant voice acting, Freberg contributed to various animation and puppetry, and his very clever and satirical radio comedy, which has never achieved the renown that it probably deserves, has developed a most devoted cult following.

One of my favorite short sketches by Freberg, which incorporates the voice comedy of both Daws Butler and June Foray, is LIttle Blue Riding Hood, a hilarious sendup of TV’s Dragnet set in the fairy tale woods.

While Freberg is known for numerous shorts like Little Blue Riding Hood, which can fit onto one side of a 45 RPM record single, he was also adept at creating longer programs, like Stan Freberg Presents The United States of America, the classic first volume of which was released in 1961. The album is a series of comic audio vignettes which make fun of various episodes of early American history. In addition to a large cast of voice actors, this album is enriched by another significant Freberg collaborator, the bandleader Billy May, who arranged the musical score. Listen to this scene from the album, which presents Freberg’s sideways take on the British surrender at the Battle of Yorktown:

Funny stuff, right? I love Freberg’s fun with the character of George Washington and lovably exaggerated British good manners, among other things. The suggestion that the Revolutionary war was won by an act of sleight-of-hand trickery is almost sacrilegious to the American myth, but this is Freberg’s world. Here’s something you may have missed: Billy May, a most facile arranger, embeds a clever touch into the music. Let’s listen more closely; watch again and go to 1:58.

What did you hear? There’s actually quite a bit going on there, but if you lend a careful ear I bet you can pick out a couple familiar tunes. There’s one in the celestra, the kind of chime like instrument, and another one in the flute. The two tunes are ingeniously played together polyphonically in one of those mystifying feats of arranging that manages to reconcile and synthesize two pieces of music with completely different harmonic and rhythmic structures, but in Billy May’s hands they sound as if they have always existed together, even as they are derived from two completely different musical works from completely different cultures. I’ve been listening to Freberg’s history of American for decades and once I started to gain a greater appreciation for music literature I began to notice touches like that. It tells me a lot about Billy May’s comic timing and problem solving abilities. Both of those tunes are frequently employed to evoke the sense of dawn and sunrise, particularly in heavy-handed comedic storytelling. May was perhaps trying to decide which tune to choose between the two, and then realized that blending both would enhance the comedy while, at the same time, giving a wink to the musical connoisseurs of the audience, of which I suspect there are many. It was a brilliant little move and it goes by so quickly. Can you hear the two different tunes? Do you know what they are? Let’s take them one at a time.

First, the chime part. Here is the original version:

The music composed by the Edvard Grieg, Norway’s greatest composer, for Henrik Ibsen’s play, Peer Gynt, has become one of those odd, and even frustrating, ironies of classical music. It is a little-known irony. Ibsen, if you don’t know him, is one of the greatest playwrights in the history of Western letters, today performed less often only than Shakespeare. Growing up with Grieg’s Peer Gynt suites, I had formed an image of the play as a quaint, enchanting folk tale rich with Norwegian lore. And while Ibsen’s Peer Gynt is largely based on Norwegian folk tales and characters, its drama is intensely philosophical, probing deeply and acutely the nature of human morality and identity, all the while couched in an unsettlingmix of myth, surreal imagery and unflinchingly dark adventure. Why, just reading a synopsis of the play is practically enough to inaugurate an existential crisis concerning a life well-lived. The Norwegian Ibsen asked his fellow countryman, Grieg, to compose incidental music for his play, both of which premiered in what is now Oslo in 1876. The irony of Grieg’s Peer Gynt music is that it now populates primarily the programs of orchestral pops concerts in the form of two four-movement suites extracted by the composer, presented primarily for the purpose of light-hearted diversion, and divorced from their original, highly challenging, contexts.

Morning Mood, which opens the first suite, is a fitting illustration. In the context of the original Peer Gynt the sun evoked by the music rose above a desolate Moroccan desert in which the title character, having been looted during the night by his unethical business associates, is left to defend himself, penniless and naked, against a horde of aggressive apes! Would you have ever formed that image from listening to Grieg’s Morning Mood out of context? I would love to catch a production of Peer Gynt with Grieg’s original score and see how that works. It is so easy to imagine a benign Norwegian sun casting its warm glow across snow-capped conifers…

In Billy May’s musical mashup which greets the day of the British surrender, there is also a flute part, presenting another familiar morning-associated tune amidst the celesta of Grieg. It is the Ranz de Vaches, a short section of the overture from the opera William Tell, about the great Swiss hero, by Gioachino Rossini. I suspect most people know that the galloping march of the Swiss Guard, the rousing finale of the overture, which has come to be associated with the Lone Ranger, hails from this overture, but I bet many of the same listeners, all of whom have heard this tune in various places as well, do not know its source. They are companions in the same composition, which was as symphonically ambitious as Rossini ever became in an opera overture, and written at the very end of his short but productive career, on the cusp of a long and cushy retirement. Read more about the fruits of Rossini’s retirement in this post.

William Tell pushes harder against the formulas that governed Rossini’s prior operatic output than any of his prior works, and this begins with the sprawling overture. Most of Rossini’s overtures are interchangeable; you could easily cut and paste the majority of these perfunctory curtain raising pieces from one opera to another and notice little effect on the overall feeling of the presentation. But William Tell’s overture is made for William Tell, and William Tell alone. Each of its 4 short movements relate to the drama in some way, achieving a level of integration that was rather ahead of its time. It would be fascinating to see where Rossini would have gone after that, but he saw fit to excuse himself from the scene after William Tell and let other ambitious and pioneering creative spirits have their say.

At this point, listen to the overture. Here is a helpful video which labels each of the four sections as they begin:

You can see that the melody quoted by Billy May in Stan Freberg’s production is from the third section. It’s funny, though, because while that melody is often associated with dawn, it is actually the first section of the overture, scored for five solo cellos, that is intended by Rossini to illustrate daybreak. It is a bleak and unsettling sunrise, though, portending strife and sorrow. The melody of the third section has been deemed suitable to depict morning in lighter settings considerably more often.

The english horn melody is a Ranz de vaches, literally “call of the cows” a brand of Swiss melody traditionally played on the alp horn while herding cows from one field to another. It has a mysterious and rich tradition. The Ranz de vaches possessed an odd and uncanny power to make Swiss folks extremely homesick, which is why it was sometimes banned from being played to Swiss troops in foreign lands, so intense was their respondent sadness and desire to desert. Rossini was not the only classical composer to imitate the Ranz de vaches. The despondent slow movement of Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique is pervaded by double reed lines meant to evoke the melodic style of the Ranz de vaches:

Incidentally Berlioz, usually quite critical of the shallow nature of the Italian operas by Rossini and his contemporaries, seemed to be more impressed with William Tell and its ambitious overture. Some listeners hear a bit of the Ranz de vaches in the idyllic opening of the final movement of Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony:

The Ranz de vaches clearly left deep resonance in the ears and hearts of Europe’s classical music.

Billy May was a smart musician, a fitting sonic companion for a smart comedian like Stan Freberg. I wonder if May knew of the rich heritage he was channeling when he so effortlessly paired Grieg and Rossini for a few seconds to greet the day on which the absurdly mild-mannered British surrendered to a cocky American general, as voiced by Freberg. The roots of both tunes run much deeper than we tend to realize as we hear them in their often unassuming contemporary contexts, heralding the dawns of so many new days as they break upon the comic stage. The suns of Grieg and Rossini rose to oversee dramatic struggles, both outward and internal. Even if you enjoy these melodies as they accompany light-hearted daybreaks in animation and pops concerts, you can keep in the back of your mind the depths of human experience concealed within the history of these well-known but little-understood classical hit tunes.

—

Would you like this featured track in your own personal collection to listen to anytime you want? Support the Smart and Soulful Blog by purchasing it here:

Or purchase the whole album, an exceptional value, here:

Want to listen to the entire playlist for this week and other weeks? Check out the Smart and Soulful YouTube Channel for weekly playlists!

Do you have feedback for me? I’d love to hear it! E-mail me at smartandsoulful@gmail.com

Do you have a comment to add to the discussion? Please leave one below and share your voice!

Subscribe to Smart and Soulful on Facebook and Twitter so you never miss a post!