The theme of this week’s Smart and Soulful blog is…Music about poultry! Every piece this week contains some illustration or reference to great birds that have been used for human food consumption. While the works in this playlist span centuries I think you will be struck by how similar the representations tend to be across styles. We’ve always been fascinated by birds and their unique mannerisms have provided musicians with inspiration and material to work into their compositions throughout human history. Some have done it almost obsessively, but for many musicians it was just the right thing to try at a certain time.

Music about Poultry, Day 3 – “Olim lacus colueram” from Carmina Burana by Carl Orff

Have you ever eaten swan? What would it mean to do that?

So, apparently people used to eat swans? http://modernfarmer.com/2014/05/come/ Not for a while though. But they were once a real delicacy, only considered suitable for aristocratic mouths. I have to figure this accounts for the thinly veiled symbolism of a certain poem written almost a millennium ago and set to music by one of the most morally enigmatic composers of the twentieth century.

The collection of poetry known as Carmina Burana was unearthed in 1803 at a Benedictine monastery in Bavaria. It was quickly recognized as a window into the soul of the Golliards, a sort of displaced and, as a result, disillusioned, second class of medieval clergy. Trained in theology and monastic disciplines at a time of overabundant applicants for a limited number of ecclesiastical positions, a large number of these seminarians found themselves adrift and questioning their place in the social order. These were the Golliards. Educated, lacking apparent purpose, world-weary, and observing around them a deep and prevalent moral corruption in the Church, they themselves gravitated toward a carnal lifestyle and expressed their frustrations over the moral degradation they witnessed in Latin verse. The Protestant Reformation was still a few centuries off, and the biting satire of their poetry was the only way the Golliards had to express their discontent. These morally charged forces would continue to build pressure under the dome and eventually explode in revolt and revolution once Martin Luther broke the camel’s back in 1517. The Golliardic poetry that survives from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries exposes many of the currents that would eventually place Luther at the door of All Saint’s Church in Wittenberg with a hammer in one hand, 95 Theses in the other, and a few nails held between his lips.

I imagine that the Golliardic poetry contained in the Carmina Burana was fascinating to many artists, historians, philosophers, and other sensitive souls in Europe during the era of the World Wars. It must have been disorienting in the extreme to experience the long reliable and effective structures of societal order and authority disintegrate around them over a matter of just a few decades. If the Dadaist art and music of the 1920s is any indication, many could relate to what the Golliards had endured almost a millennium earlier, that had resulted in their disillusionment and moral laziness. Add to that a sense of underlying dread, even approaching nihilism, and you can easily arrive at the Dadaist sensibility with its absurd and disturbing imagery. Germans in the 1920s were disheartened, depressed, uncertain, and in need of something new to believe in. Their music and art expresses this all too clearly. In addition to the age of Dada, it was also the age of the cabaret with its gleeful and exhibitionistic disregard for conservative morality, and also the bracing, cerebral music of composers like Hindemith and Schoenberg which commented on the feeling of the time in its own way, with equal measures of academic rigor and angst. As we know Nazism all too easily slipped into social void and began to develop a new and powerful style of authority that quickly began to rebuild the shattered nation, which most of its citizens were all to happy to go along with, even without fully realizing what was in the movement’s heart and how it would be tragically expressed over the decades to come.

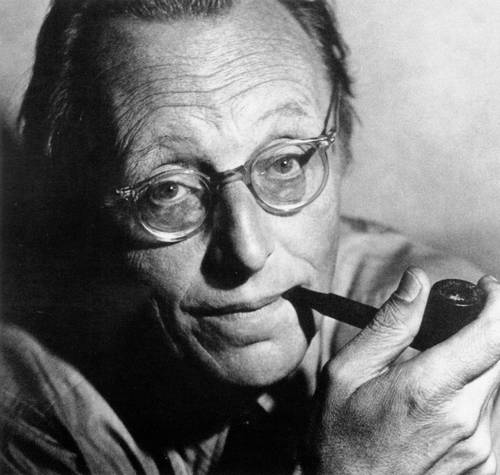

Carl Orff occupies a place in all of that that I find frankly difficult to judge definitively. He lived through that most disorienting time, and seemed to support the aims of the Nazi regime, which ran its entire course during his adult years. While Nazism had its detractors, both societal and artistic (those who refused to create art in line within the regime’s accepted guidelines) Orff was not one of them. But how harshly can we judge him for this? How harshly can we judge anyone for not speaking out, especially when it is so hard to say how clearly people saw the appalling fruits of Nazism on a day-to-day basis? People need to live, after all, and it is so easy to become wrapped up in the pursuit of getting along. And who isn’t suspicious or distrustful of their governing authorities from time to time?

There are those stories that make one wonder if he should have taken notice and committed to greater self-sacrifice in the name of social justice. When the Third Reich banned Felix Mendelssohn’s incidental music to A Midsummer Night’s Dream (because he was born Jewish, even though he later converted to Luther’s sect) and called for German composers to create new, comparable works, Orff answered their call. And then there was the time that Kurt Huber’s wife asked Orff to defend him. Professor Huber was one of the founders of The White Rose, a college-based organization that secretly resisted Nazism, and he was eventually caught and captured. Shortly after that Huber’s wife pleaded with Orff to use his influence and favor with the Reich to advocate for him, but he refused and Huber was executed. Should he have complied? Would he have made a difference? Would he have been hurt by the scandal himself? Hard to say. And hard to ultimately judge him definitely on this matter, although people keep looking deeper in an attempt to do so. He was deeply remorseful over this later on.

We could have similar discussions about other figures like Richard Strauss. These artists, working within the Nazi Party’s accepted practices, survived because they toed the cultural line, and their reputations survive because they kept their compliance and support for the regime ambiguous enough to escape definitive judgement. Still, it is not without certain irony I realize that I spent so much time in my elementary school music classes playing Orff instruments under teachers devoted to Orff Shulwerk while, just a handful of decades before, many of my ancestors had suffered and died in Nazi camps. I’ve even composed music for Orff ensemble, which I enjoyed very much, but in thinking through the way these things interrelate it is easy to become conflicted.

However we judge figures like Orff and Strauss, their music is still with us and delights its listeners. I wonder, though, what it was exactly about the texts of the Carmina Burana that attracted Orff’s attention and caused him to deem them suitable for a musical setting in Germany during the late 1930s. Was there some part of him that was suspicious of the rising regime? Did he sense a similar hypocrisy to that observed by the Golliards centuries earlier? Was he reacting to the moral degradation of the Dadaist age? It’s hard to say, but in listening to Orff’s setting of Carmina Burana, in addition to the powerful Germanic force that so clearly pervades certain movements, and would have resonated with the Nazis (like the immediately recognizable opening chorus, although it is clear the Nazi party was not receptive to the intended lesson of the text), I hear an almost grotesquely ironic, and even cabaret quality in others. Like this one:

Once I lived on lakes,

once I looked beautiful

when I was a swan.

(Male chorus)

Misery me!

Now black

and roasting fiercely!

(Tenor)

The servant is turning me on the spit;

I am burning fiercely on the pyre:

the steward now serves me up.

(Male Chorus)

Misery me!

Now black

and roasting fiercely!

(Tenor)

Now I lie on a plate,

and cannot fly anymore,

I see bared teeth:

(Male Chorus)

Misery me!

Now black

and roasting fiercely!

Do you hear that chiding chorus, sympathizing with the Swan’s demise? The swan was once a thing of sublime beauty, gracing the lakes upon which it swam. But was it too prideful? It is now in misery, roasted black on a spit. And the chorus echoes the tenor swan “Misery me!”, but in the most ironic and parodistic way. The Golliard’s message is clear: pride goeth before a fall; beauty and honor inevitably end up in ruins, a pattern that plays out again and again in our fallen world. Of course the Third Reich thought itself immune, quite mistakenly. Could Orff see into the future, even in 1936 before any of that would have been clear?

—

Would you like Aaron of Smart and Soulful Music to provide customized program notes especially for your next performance? Super! Just click here to get started.

Would you like this featured track in your own personal collection to listen to anytime you want? Support the Smart and Soulful Blog by purchasing it here:

Or purchase the whole album, an exceptional value, here:

Want to listen to the entire playlist for this week and other weeks? Check out the Smart and Soulful YouTube Channel for weekly playlists!

Do you have feedback for me? I’d love to hear it! E-mail me at smartandsoulful@gmail.com

Do you have a comment to add to the discussion? Please leave one below and share your voice!

Subscribe to Smart and Soulful on Facebook and Twitter so you never miss a post!