This week’s theme is…Mountains! The stoic, majestic guardians of Earth’s geography, mountains have long inspired musicians with their monumental presence. This week we examine some examples of this.

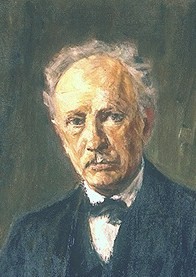

Mountains, Day 4 – Yea, cast me from Heights of the Mountains by Edward Elgar

Warning: This post contains some material that parents of young children may want to screen before showing.

It’s been a while, but I still remember how much fun it was to watch the show Glee on TV.

I’ll bet you’ve seen at least a few episodes, and if not, then I’m sure you’re familiar with some of the musical arrangements, which became a cultural phenomenon all their own, even independently of the show. I think I watched the first couple seasons or so around 2010, and found them captivating before I eventually decided to move on. But during the seasons that I watched the show’s clever combination of high-school soap opera drama, overacting from attractive actors, and top-notch musical productions made for a delicious mix indeed. It is self-consciously over the top, wearing heavy-handed melodrama upon its sleeve, and reveling in the obvious absurdity of high-schoolers creating performance after performance for approval of their teacher that would be impressive even when executed by professionals. That high school should have been world-famous given the quality of its music program 🙂 But that’s part of the fun, of course. Glee managed to be an addictive high school drama, serial musical, and bandstand showcase all rolled into one.

It was always intriguing to see which popular tunes of the past few decades the musical directors of the show would choose for their productions. The selections ran the gamut, widely varied in both decade of origin and style. And many songs found new life in the ecstatic and energetic covers by the cast of Glee. Here’s one that stands out in my mind:

After watching that episode I remember hopping onto Amazon and ordering albums by Marky Mark, Parliament, and the Commodores, something I would never have thought to do otherwise.

I’m not sure how the show got its name, but I’ve always been struck by its inaccuracy. It has a great ring to it, but the show would more precisely be called “Show Choir”, as that’s more or less what these performances are. “Glee” refers to a very specific genre of music, and one that is never actually heard in Glee. At least, not that I ever remember.

Henry Purcell was the greatest composer of England’s baroque era. In his 36 years on Earth he wrote copious amounts of music in his very quirky and distinctive voice that has been recognized as the greatest work by a native Englishman until Edward Elgar, more than two centuries later. If you hear Purcell on a concert, chances are it will be his noble opera Dido and Aeneas (see this post for an excerpt from that) or one of his massive odes for chorus and orchestra, suitable to be played at a royal court. But, Purcell had another side as well; a very different side, and a side very much worth getting to know. Henry Purcell, as Englishmen still do, enjoyed his time in the pub, drinking pints with his mates. And there were no jukeboxes in 1680, so if you wanted some music with your bitter you needed to make it. And so Purcell and many of his colleagues lent their considerable creative skills to the generation of very clever and very bawdy drinking songs, some of the finest crafted ribaldry in Western history. Think Shakespearian insults, but in music. Here’s a terrific example by Purcell’s surviving contemporary, John Isham, like Purcell a serious composer who also enjoyed his time in the ale house. It’s called “Celia Learning on the Spinnet” and describes the title character’s lesson upon the instrument with her much older, male teacher. I get the sense some of the words of the text have multiple meanings…

Cute? I hope you are not too scandalized by that. And it’s just one example of a host of such silly and licentious musical numbers penned to be sung by Englishmen letting their hair down together. If you want to explore some more of these, try either of these albums:

This particular song is of a genre known as the catch, essentially a round at the unison with different entrances, often on bawdy texts. A clever composer like Purcell or Isham could find ways to make the music serve the text effectively, just as in Ceclia where the gaps in the first verse allow a…certain phrase to ring through as successive voices are added.

Catches are great fun if you’re playin’ with the boys.

But what if you’re in mixed company? Well, you would probably want a classier text, and this kind of song was the glee, also British. Where catches are polyphonic, with multiple independent voices darting all over the place, glees tend to be homophonic, which means it sounds more like a church hymn, with multiple voices singing in more or less the same rhythm. In the Romantic era, glee clubs sprang up all over Britain, and then emigrated to the United States. You’ve probably heard of glee clubs at Ivy League schools, staffed by classy gentlemen singing charming and straight-laced love songs. In movies their presence is often used, intentionally or not, to evoke feelings of tradition and social order, which makes a great deal of sense given that glees and glee clubs originated in a country that so prizes that kind of thing.

In the late nineteenth century the young British musician, Edward Elgar, was just beginning to make his presence felt, working in his father’s music shop, performing on the violin, accompanying, teaching lessons, and beginning to compose and arrange in Worcester. He was also a member of the city’s glee club, which he was eventually to lead. Elgar is today known for his quintessentially British-sounding orchestral and choral music, particularly his marches, concertos, symphonies and grand oratorios, which successfully meld Handelian and Wagnerian influences. But the glees remained close to his heart, and he made his mark composing English part songs. Here is a lovely example, the first of what is known as the Greek Anthology, Opus 45:

Elgar’s text setting is direct and clear, wielding the resources of his all-male choir with utmost efficiency. These part songs demonstrate a composer’s skill in settings that feel considerably less “immortal” than the great symphonies and operas so fundamental to the history of music. See examples of such lighter fare by other composers here and here. It is often rewarding to lend our ears to the small, everyday works that so easily become lost in the cracks between the great monuments, but that exhibit skillful craftsmanship and impeccable artistry on smaller and much less ambitious scales. This is the magic of genres like the glee and the catch, and has been for centuries.

—

Would you like Aaron of Smart and Soulful Music to provide customized program notes especially for your next performance? Super! Just click here to get started.

Want to listen to the entire playlist for this week and other weeks? Check out the Smart and Soulful YouTube Channel for weekly playlists!

Do you have feedback for me? I’d love to hear it! E-mail me at smartandsoulful@gmail.com

Do you have a comment to add to the discussion? Please leave one below and share your voice!

Subscribe to Smart and Soulful on Facebook and Twitter so you never miss a post!