This week’s theme is…Music about Transportation! When we hear the word “transportation” in the twenty-first century, we imagine many modes of moving people and things from place to place, over sea, land and air. This is largely a modern set of images, although people and things have moved from place to place throughout all of history. Because of this, the theme of transportation is present in music to varying degrees through its history.

Music about Transportation, Day 1 – Short Ride In A Fast Machine by John Adams

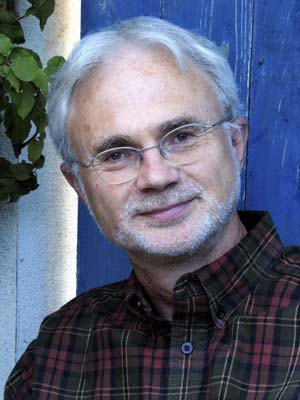

The modern musical style known as minimalism is an essentially American style, and a living one, even aging as it is. As of this writing all of its most influential creative leaders are still with us, many of them still at work. Younger composers look to the minimalists for inspiration and many have tried their hand at creating their own minimalist works in the mold of their heroes, even if there has not been anyone who has emerged to continue the movement as forcefully as its current luminaries. Here is my own attempt. Written more than a decade ago, it is heavily indebted to Philip Glass and remains to this day one of my best-received works:

Many music historians see minimalism as a response to the overly cerebral and inaccessible assault (forgive me!) of serialism that popped up after the Second World War and dominated Western art music for more than 3 decades. American composers began to experiment with the styles and techniques that would become minimalism in the mid-60s, with more fully mature efforts by the three most successful composers of the style, Philip Glass, Steve Reich and John Adams, coming in the 70s and 80s. It is easy to understand why minimalism is often regarded as an “opposite” of serialism; it is everything that serialism is not: diatonic, repetitive, consonant, accessible, easy even. Its simplified tonal and rhythmic elements share many commonalities with much popular music and so the membrane between the two styles was easily permeated. For minimalists sounds you can look to bands like Can, Velvet Underground and even, some might say, odd later works from the Beach Boys.

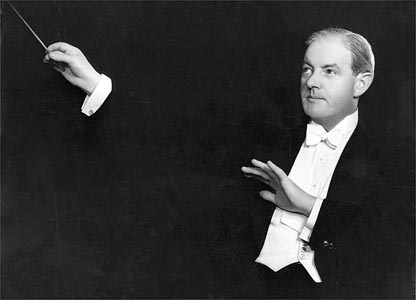

Observers from my vantage point, and those similar, have had the opportunity to watch the stylistic movement grow and morph within our lifetimes, and to see the “big 3” (Glass, Reich and Adams) flourish and develop into unique artists with quite distinctive voices, even if there is still ample reason to group them together under the same minimalist umbrella. Fans of minimalism could easily distinguish by ear music from any of the three, so different are they in their characteristic procedures and idioms. Of the three, John Adams is most often described as taking minimalism as a “foundation” but not always sticking to it strictly. If you listen to anything, even recent music, from Glass or Reich (Glass’ film scores excepted) you will see how it sticks more or less to the highly repetitive mold, almost obsessively so. But Adams, while his music certainly bears marks of minimalism, seems more comfortable to mix it with other moods and romantic gestures. It is just a little less certain what you will hear from Adams than the other two. I’ve even heard a nifty all-electronic album from John Adams, and you can listen to this interesting NPR story which notes many points of confluence between John Adams and Beethoven’s music. You just wouldn’t see anyone make that comparison with Glass or Reich. But Adams is able to compare Beethoven to minimalism for his amazing economy of means- Beethoven’s ability to suck the marrow out of tiny, motivic ideas. I have noticed that there is a fair amount of obsessive repetition in Beethoven (listen to the first movement of the Pastoral Symphony). It seems Adams might say that he was influenced by minimalism, even if he was never a bona-fide minimalist like other composers. And this distinction would allow him to remain flexible, with a broad stylistic base from which to pull at various times depending on the intent and situation. Some of Adam’s works are quite genuinely minimalist, and most effectively so (like Shaker Loops, for example, a terrifically affecting work for string orchestra). But from the very beginning Adams incorporated minimalism into his general tapestry with far more diversity than those with whom he is commonly lumped together as the “minimalists”.

One of his most famous works, still popular today, 30 years after its creation, is the orchestral fanfare Short Ride In A Fast Machine. This brief fanfare is a great way to become acclimated to John Adams’ “postminimalist” style, in which he combines elements of minimalism with a broader orchestral scope and class of gestures. If you enjoy this, I would encourage you to explore some of his larger orchestral works, of which there are quite a few, and quite varied.

The tapping woodblock which pervades the first half of the piece is its most obvious feature, but try to listen past that to the brilliant woodwind flourishes that fill the air and the chugging brass syncopations which are gradually passed to the strings and serve to elevate the piece to its first climax in energy, punctuated by a martial statement of percussion. After the opening energy dies down a most intriguing section begins in which the lower instruments of the orchestra, trombones, bassoons, cellos, double basses, take on a greater agility than to which they are typically accustomed and begin to create a rising, insistent musical line that eventually carries the piece to its turbulent climax. And then, something truly stunning: with about a minute of the remaining, the woodblock finally stops, and the orchestra produces a new texture, evoking a new landscape. Broader, calmer, peaceful. Still fast-moving, but more like the eye of the storm. Or gorgeous flat terrain that opens up about the traveler in the fast machine. The strings play a steady ostinato of short, repeated notes, as the brass play a chorale-like tower rising out of the ground, higher and higher, just before a reprise of the opening fanfares brings the piece to an abrupt conclusion.

I have long listened to this piece and marveled at the immersive pictures it has created in my imagination. I have been enraptured by abstract, colorful panoramas that seem to fly by as I levitate in some kind of floating craft to which the laws of physics simply cannot apply, and the final placid minute evokes the most magically-textured landscapes. I must confess a tinge of disappointment in recently learning of Adams’ actual experiential model for Short Ride In A Fast Machine…

I don’t know, it just doesn’t seem like it fits to me. He may say he didn’t like the ride, but I don’t think the music does. It is constantly full of wonder, excitement, elation, amazement. So, I think I’ll stick with my original concept as described in the previous paragraph, because that’s still where I go in my imagination as I engage with Short Ride In A Fast Machine. And I don’t think I’m the only one. Watch Victor Craven’s splendid animation and see if you don’t think his abstract and beautiful take fits like a glove and follows the pacing most precisely, no sports cars necessary!

—

Would you like this featured track in your own personal collection to listen to anytime you want? Support the Smart and Soulful Blog by purchasing it here:

Or purchase the whole album, an exceptional value, here:

Want to listen to the entire playlist for this week and other weeks? Check out the Smart and Soulful YouTube Channel for weekly playlists!

Do you have feedback for me? I’d love to hear it! E-mail me at smartandsoulful@gmail.com

Do you have a comment to add to the discussion? Please leave one below and share your voice!

Subscribe to Smart and Soulful on Facebook and Twitter so you never miss a post!