This week’s theme is…Music About Fireworks! Is there anything more festive than colorful, explosive fireworks? For centuries we have been celebrating with fireworks, and for just as long they have been inspiring equally colorful and explosive music. This week we learn about some examples of this.

Music About Fireworks, Day 2 – Fireworks from the Second Book of Preludes by Claude Debussy

The keyboard family of instruments all share a common method of input, but their acoustical mechanics and consequent idioms could not be more different. With all of these instruments the player uses his digits to select the pitches he desires the instruments to speak, and the motion and finger shape are essentially the same. But, if you look inside, the processes by which the sound is stimulated, amplified, and ceased unfold in very different manners, inviting comparisons with other instruments that do not have keyboards.

If you hear an organ, the player’s fingers are controlling valves which permit or prevent the flow of air through pipes which resonate like flutes, trumpets, or other wind instruments. So the organ is essentially like a great wind ensemble controlled by a keyboard. Consequently, organs require an air supply, which is facilitated either by a human pumping a bellows, as it was during Bach’s day, or an electric machine as is typically done today – insert commentary about machines doing the job of men!).

If you hear a harpsichord, the keys are used to play what is essentially a guitar, lute or harp within the instrument’s cabinet. The keys trigger what are very much like miniature guitar picks called plectra (singular plectrum) and the resulting texture, alive with countless points of sound, is akin to some wicked finger work upon a plucked string instrument:

And if you hear a piano the mechanism is yet different. When one strikes a key upon a piano he sets into motion an intricate lever which brings the felt-covered head of a small hammer into contact with a string, much thicker and more powerful than those of the harpsichord. For this reason the piano is often classified as a percussion instrument, even though we don’t tend to think of it in these terms.

The action of the piano proved to be the most flexible of all keyboard instruments, affording performers unprecedented control over the color and volume of their sound. As a result it quickly eclipsed its other keyboard instrument cousins during eighteenth century, emerging as the preferred medium for the keyboard composers in Europe at this time. Bach didn’t like them, although he may have been too conditioned by his considerable experience with the harpsichord and organ to keep an open mind as he tried some of the early models. Also, the piano underwent rapid and dramatic changes during its early years which vastly improved upon its already impressive flexibility and versatility. But Europe went piano crazy, and the Western world is still piano crazy. Every new generation finds a new way to speak upon the piano which is simultaneously well-suited for the instrument and distinct from its ancestors (see this post).

This trend goes back to the very beginning. The piano’s capabilities allowed composers to speak upon it in a song-like legato quite distinct from the lively pins and needles of the harpsichord. The piano of the classical era sung like a human voice with smooth lines and dynamic shapes. The Romantics who followed split into two directions – there was the percussiveness of Beethoven’s school and the soft, velvety textures of Chopin (see this post). This is not necessarily a binary distinction – Beethoven could be quite lyrical and Chopin could be quite turbulent. But it is more or less and apt distinction. Beethoven went on to inform the German manner of playing, percussive and dramatic, and Chopin the French, elegant and mellifluous. They are both still quite popular, although Beethoven is sometimes spoken of in near-religious terms that Chopin is not. This may very well be a German thing, as the they have been apt to spiritualize their music and musical experiences. Hans von Bulow once said that Bach’s Well Tempered Clavier is the Old Testament (see this post) and Beethoven’s 32 piano sonatas the New.

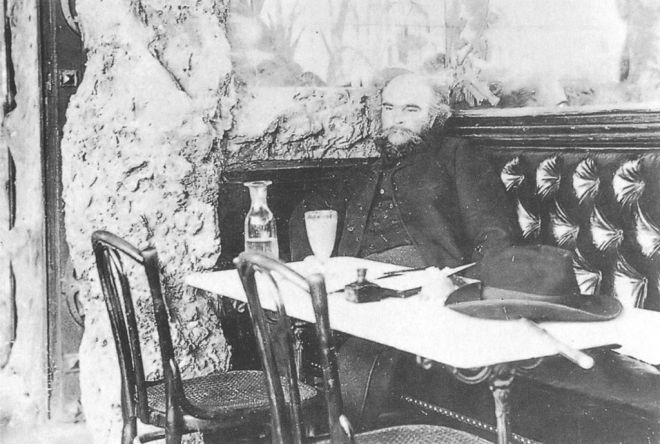

It may have seemed at the time that Beethoven and Chopin had collectively managed to exhaust the piano’s potential for color and expressive possibilities, but in the early twentieth century a French composer seemed to know there was territory yet to be uncovered. By the turn of the century Claude Debussy, something of a maverick, had already demonstrated his penchant for blazing ahead without the baggage of traditional forms and harmonies. He had found colors and gestures within the symphony orchestra that most had not known to exist (see this post). A gifted and virtuosic pianist, he had written steadily for that instrument also. Accounts of his playing indicate that it was mesmerizing, almost as though his fingers melted through the keys and delicately touched the strings themselves, transcending the mechanical realities of the instrument. Just as magical was his use of the sustain pedal, about which he seemed to have some kind of special, miraculous insight. And he had strong words for the hallowed names of the German piano tradition:

“I heartily detest the piano concertos of Mozart, but less than those of Beethoven. I became finally and completely convinced that Beethoven definitely wrote badly for the piano.”

Words like this seem audacious, even arrogant to us. Beethoven is such a sacred cow. But perhaps in order to create something new Debussy needed to break, and even disparage the giants of the past in order to break free and breathe anew. And breathe anew he did. In the two books of Preludes for solo piano composed in the early 1910s Debussy shows us colors and textures within the piano that were not known to exist, just as he had done with the symphony orchestra.

Each of the Preludes evokes an image through some kind of texture or harmonic scheme, colorful, novel images alive with cloudy mist. Sometimes gentle, sometimes ecstatic, sometimes kinetic, sometimes calm, always novel and with a most imaginative dimension. Each Prelude is subtitled, but Debussy placed the title at the end of the movement so as not to prejudice the performer with an unwarranted image during performance (of course this could only be short-lived – everyone knows the titles now!). Debussy ended the whole collection of Preludes with a fantastic, frenetic movement called Fireworks. From the very beginning the colors and shapes captivate us, illustrating clouds of smoke, smoldering fuses, and whizzing rockets:

The piano still dominates the world’s keyboard instruments. Shortly after its invention, even in its early, imperfect state, its near limitless expressive potential was evident to all who played and heard it. Every generation seems to find its own way to relate to the keys of the piano, forming its own distinctive palette of colors and shapes. Perhaps none have been as colorful or evocative as the colors and shapes of Claude Debussy’s pianism, his stunning impressionist palette revealing what no one could ever have expected within the strings and hammers of the instrument. Indeed, it seems to have been necessary for him to evaluate and ultimately judge some of the greatest music for the piano as inadequate, as strangely as that strikes so many of us, to hear and to ultimately liberate his vision from the strings of the piano.

—

Would you like Aaron of Smart and Soulful Music to provide customized program notes especially for your next performance? Super! Just click here to get started.

Want to listen to the entire playlist for this week and other weeks? Check out the Smart and Soulful YouTube Channel for weekly playlists!

Do you have feedback for me? I’d love to hear it! E-mail me at smartandsoulful@gmail.com

Do you have a comment to add to the discussion? Please leave one below and share your voice!

Subscribe to Smart and Soulful on Facebook and Twitter so you never miss a post!