This week’s theme is…Stormy Scherzi! A scherzo is traditionally defined as a “musical joke”, that is, a light-hearted movement that lacks the weight of a good sonata form essay. And often that’s how they feel. But, have you ever listened to a “scherzo” that seemed to fit the description of a musical joke, but darkly? Some scherzi paradoxically combine lightness with intensely determined feelings, sometimes even bordering on malice and despair. This week we examine some such examples.

Stormy Scherzi, Day 3 – Scherzo for X-Wings from The Force Awakens by John Williams

Disclaimer: This post contains spoilers regarding elements of Star Wars: The Force Awakens. If you have not yet seen the film and wish to have a fresh experience when you do, I would advise waiting until you have to read this post.

If you have been at all curious about my reaction to Star Wars: The Force Awakens, then today is your lucky day! I can’t imagine why you would, but maybe that comment demonstrates unwarranted self-effacement. I suppose my opinion is as valid as anyone’s. So here goes. I’ll start with my general experience of the Star Wars franchise…

I was born in the early 1980s, and my dad had a way of showing me trendy movies that I may not have been psychologically mature enough to process. I remember being fed a diet of Star Wars and Top Gun, all prior to the age of 6, definitely too young for Top Gun and probably too early for Star Wars. The earliest memories of my experience with Star Wars are two-fold: one is being terrified of Ponda Baba’s severed arm in the Cantina scene in A New Hope…

…and the other is entering a movie theater to see a shot of C-3PO and R2D2 framed by the trees of Endor in Return of the Jedi. Between the islands of that memory archipelago are certainly abundant other experiences, but they have since been covered by the ocean of age. Those two isolated images are my earliest memories of Star Wars.

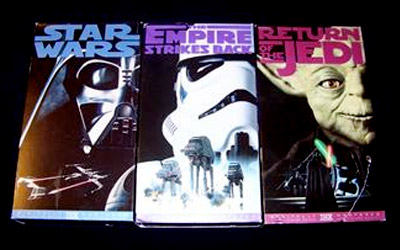

About a decade or so later my brother and I began to take an interest in the film franchise, fueled largely by the effusive praise of a teenage babysitter. This was around the time that the films were remastered and re-released on VHS, including extensive interviews between George Lucas and Leonard Maltin which preceded the films, and ended up being fast forwarded through rather often:

And that was mostly how we watched them during my teenage years. We enjoyed them, and were definitely fans, although not fanatically so (insert your interpretation of “fanatical” here).

And then the prequels came out in the early 2000s. I retain strong memories of two qualities of that whole experience: one was that I was underwhelmed by the films in general, especially for their acting, the cold CGI, and also the materialistic shattering of the mystery of the Force (midi-chlorians and all that), and the other is being struck by how consistent John Williams’ musical score felt with the original trilogy (Dual of the Fates aside; I wasn’t crazy about that number). I remember having discussions with fellow musicians, and probably reading articles, that expressed sentiments to the effect of “George Lucas seems to have lost something, but John Williams still has it!” That seemed about right to me. I may revisit the prequel trilogy in the coming months if I get a chance, just to see if there is any room for re-evaluation, but I wager that most people can agree that Williams provided a crucial glue to mesh the two trilogies in spite of the inconsistencies many members of the audience noted in other aspects of the film making.

John Williams’ work in all of the scores of the Star Wars canon is often compared to the orchestral music of Wagner’s Ring tetralogy, a thick, overarching, blanket of connective tissue rich with symbolic musical motives associated with characters and philosophical themes which serve to captivate listeners/viewers and reinforce the semiotic interrelatedness of the story and its actors. For more on Wagner’s artistry see this post and this one. The comparison is apt – Williams has clearly been a keen student of Wagner’s leitmotiv technique and instinctively knew to apply it to the Star Wars films, even before he was certain that sequels were in the cards. The difference, I suppose, is that Wagner’s creative vision remained consistent in all aspects of the Ring over the course of the few decades he took to complete it, be it libretto, characterization, dramatic pacing, music, etc. But in the Star Wars films the consistency of Williams’ music exceeds that of many of the other elements, particularly as you look from trilogy to trilogy, and now beyond. Whoever ultimately owns the Star Wars brand ought to be very thankful for Williams’ ongoing involvement and the continuity it has helped to facilitate between films.

I would assert that Williams’ contribution is indeed the strongest element of The Force Awakens, just as it is in the prequel trilogy. I viewed this trailer many times in anticipation of the return to the good ol’ days of the original trilogy that it promised:

Even in this brief trailer it is the music that evokes the most powerful response of any of its elements. After an extended layering of the initial harmonic progression (E: I – iv – N6 – I, or E – Am – F6 – E for all you theory geeks in da house) during which the arguments of the drama are presented, a significant theme first heard in Episode V, The Empire Strikes Back, known as the love theme between Han Solo and Princess Leia, peals forth measuredly and deliberately from violins in their lowest register, just as we see the dogfight between tie fighters and the Millennium Falcon and hear Han Solo, grizzled with age and life’s adventures, affirm the veracity of the legends of the Jedi and the Dark Side. This was the very moment that sold me on the film and I still remember my internal emotional response as I viewed this trailer for the first time in December of 2015. In fact, I still respond to it in much the same way now. After that, we hear two other leitmotivs: the stoic Force theme, first heard in Episode IV, A New Hope, which plays as we catch our first glimpse of a battle-ready Kylo Ren, wielding his distinctive cross-shaped lightsaber, and finally a hushed statement of the Star Wars main theme just as the trailer ends and the title of the film drifts away before us.

Would the trailer be as effective without Williams’ well-placed musical cues? I’m sure I don’t need to answer that question. The compelling themes and motives of the Star Wars universe are probably the best tool at its marketers’ disposal. Even as new characters are added, to varying degrees of success, Williams comes out on top with brilliant themes that manage to sum them up, and this is true of both the prequel trilogy and The Force Awakens.

I was similarly underwhelmed by The Force Awakens as the prequel trilogy, but for different reasons. I felt, as did many critics, that it more or less told the story of A New Hope and pandered to fans of the original trilogy with heavy-handed references, and quickly became frustrated and disinterested. But at least the music provided much-needed continuity with the other films. And Williams even managed to have a little fun with the material. What a clever touch to include a playful and turbulent “Scherzo for X-Wings” for some of the final dog fighting, rife with contrapuntal maneuvering of the Star Wars Fanfare:

The title is almost like a packaging, earmarking it as an obvious choice as a self-contained concert number for accomplished bands:

Does the Scherzo for X-Wings take its place among classic Star Wars set pieces like “Here They Come!” or “The Asteroid Field”? Hard to say, and only time will tell. But it is a fine example of the crucial cohesion provided by John Williams’ solid contributions over the course of a decades-long effort to produce a coherent universe of storytelling which has come to be filled with other elements that have fallen short of the original in that regard. Williams truly speaks to the souls of Star Wars fans; he seems to understand and acknowledge the gravity of the covenant he made with his current and future audience back in 1977 and continues to honor it to this day with his considerable abilities of orchestration and musical characterization.

—

Would you like Aaron of Smart and Soulful Music to provide customized program notes especially for your next performance? Super! Just click here to get started.

Want to listen to the entire playlist for this week and other weeks? Check out the Smart and Soulful YouTube Channel for weekly playlists!

Do you have feedback for me? I’d love to hear it! E-mail me at smartandsoulful@gmail.com

Do you have a comment to add to the discussion? Please leave one below and share your voice!

Subscribe to Smart and Soulful on Facebook and Twitter so you never miss a post!