This week’s theme is…Shuffling Off! Musicians are human, and humans die, often with works in progress. These unfinished works form a tantalizing “what would have been”. Sometimes they are finished by crafty folks who aim for the double bar. Sometimes it is interesting to listen to them as they remain, a fascinating window into the creative process of a genius, cut short by the mortality we all share.

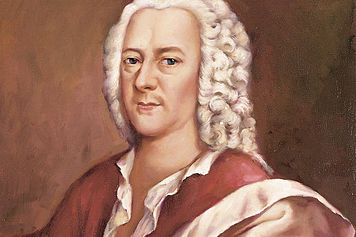

Shuffling Off, Day 2 – Contrapunctus XIV from “The Art of Fugue” by Johann Sebastian Bach

Do you have an “elevator speech” prepared? An elevator speech refers to a pithy sales pitch or description of services that is brief enough to deliver to a captive audience during a short elevator ride, but substantive enough to give a complete impression of doing business with you and persuasive enough to move a prospect toward closing a sale or referring someone else to do the same. Business professionals of all stripes are encouraged to prepare such elevator speeches with the aim of turning any short meeting into closed business. You can think of an elevator speech as a personal abstract, a concise summary of what you are about that gives the broadest overview as clearly as possible. A good elevator speech should provide a vivid image of what working with you is like, but leave enough to the imagination that the prospect is intrigued to take further steps to making this a reality and filling in the outlines it draws.

Sometimes when I read articles about notable composers in the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, the gold standard for general research about practically any topic in Western art music, I note that the authors are, in many ways, creating elevator speeches for them. Actually, they are not so much about the composers themselves as their legacies. If you had met Handel on the street his description of services would be somewhat different than the way we have come to describe the legacy left by his life and body of work. When the Grove’s authors write their introductions they are essentially summarizing why we value these musicians and the benefits acquaintance with their work can offer to us, even after multiple centuries. While the gigantic articles about significant composers are packed with interesting biographical and artistic detail, I often find the little abstracts which precede them to be the most clever and carefully written parts of the article. And I think my favorite abstract in the Grove’s, one to which I return again and again out of admiration, is that about Johann Sebastian Bach. His article warrants 55 pages, and its author, Christoph Wolff, summarizes the old master’s legacy thus:

His genius combined outstanding performing musicianship with supreme creative powers in which forceful original inventiveness and intellectual control are perfectly balanced.

While it was in the former capacity, as a virtuoso, that in his lifetime he acquired an almost legendary fame, it is the latter virtues and accomplishments, as a composer, that have earned him a unique historical position. His art was of an encyclopedic nature, drawing together and surmounting the techniques, styles and general achievements of his own and earlier generations which later ages have received and understood in a great variety of ways.

It is densely written and requires considerable study to unpack and appreciate. But it is also very effectively summarizes what we value about Bach. Can you imagine him walking around with business cards on which are printed:

Johann Sebastian Bach, organist and composer

My genius combines outstanding performing musicianship with supreme creative posers in which forceful original inventiveness and intellectual control are perfectly balanced

Of course not. Don’t be ridiculous! Like I said, that’s his legacy. But let’s take that apart:

Outstanding performing musicianship – I think what this means is that for Bach there was little distinction between performing, improvising, and composing. As a performer and composer, he was constantly inventive and completely at home, going between them with ease and grace.

Supreme creative powers – That’s a strong word, even a superlative one. What Wolff is saying here is that no one in the history of music was more creative than Bach, who could create quickly and consistently, and with astounding inspiration, any time any place.

Forceful, originally inventiveness – If you have listened to any amount of Bach and paid attention, perhaps you have been struck by the cascade of remarkably vigorous and finely-wrought musical ideas which are always distinctive, but always speaking clearly in Bach’s voice. It never ends, nor does the strength with which they are asserted.

Intellectual control – Bach is still heralded as the most intelligent musician ever to live. Had he been a mathematician or physicist, he would have rivaled Newton and Einstein. As an author he would have contended with Shakespeare. Once you know a little bit of how music works it is simply mind-boggling how controlled Bach’s music is on every single level, and consistently so.

Do you get the picture? It is easy to divinize Bach, but the image I often carry of his music is like that of a god (or a demigod at least), creation full of beauty, detail and inner consistency springing from his mighty finger (see this post). Bach’s music really does feel like some kind of eternal stream flowing from the source of the very forces that bind the universe. I think that is what Wolff is saying in his summary.

But Bach was not a god; he was mortal. And in one particular piece we hear his god-like stream of creation come to a very human halt. At the end of his life Bach created a collection of fugues and canons all on the same subject, something of a catalog of contrapuntal techniques. The resulting Art of Fugue, if not necessarily loved, is respected by musicians for the feat of superlative craftsmanship and invention that it is. Bach did not live to complete his vision. He came very close, but the final fugue, which promised to work upon four different subjects, evokes the image of Bach’s life force finally and completely ceasing:

Can you hear all the elements of Wolff’s description, working in full-bodied force, and suddenly stopping? From this it seems that Bach’s musicianship sprang complete from his spirit with no necessary refinement by his ears or external editor of any kind. In a way it is almost a blessing for this to stay unfinished, a fitting image of the valve that closed when Bach died and stopped the flow of the consistent eternal creative force which he had learned to channel.

I’m not sure what Bach’s elevator speech would have been during his lifetime, but I think Christoph Wolff came up with a pretty good one for his legacy. The qualities Wolff describes are constantly present in every single bar of music composed by the mature Bach. I once played a chamber piece by Bach, coached by a university professor. I was astounded by the constant inventiveness of the music and he noticed this. He said something like “Yeah, there’s just constantly amazing things happening. The guy was from another planet!” He wasn’t, but it can often seem that way. He was mortal after all, and the final fugue of the Art of Fugue shows us this plainly, if tragically, placing the god-like Bach in real space and time.

—

Would you like Aaron to provide customized program notes especially for your next performance? Super! Just click here to get started.

Want to listen to the entire playlist for this week and other weeks? Check out the Smart and Soulful YouTube Channel for weekly playlists!

Do you have feedback for me? I’d love to hear it! E-mail me at smartandsoulful@gmail.com

Do you have a comment to add to the discussion? Please leave one below and share your voice!

Subscribe to Smart and Soulful on Facebook and Twitter so you never miss a post!